Anodyne

April 10, 2021

(CW for some horror-ish stuff, plus big spoilers for Anodyne 2.)

My senior seminar was a class on time travel in the “literary imagination,” a wide-ranging survey of the speculative plot device’s use starting with H.G. Wells’ seminal Time Machine in 1985, and ending on some stuff released in the last decade. For our final paper, the meaning of “literary” was a pretty open definition when it came to what works to dissect—so, naturally, I decided to use Wells’ novella along with Marge Piercy’s 1976 novel Woman on the Edge of time to posit “apocalyptic time travel narratives are inherently environmentalist, therefore 90s JRPGs are good, actually.” If time travel and 90s JRPG wasn’t immediately telling, the last couple works involved were Chrono Trigger and its black sheep of a sequel, Chrono Cross, with a big emphasis on the latter (along with a smattering of Final Fantasy VII for that extra prestige spice).

I did pretty well on the paper, but I don’t consider it to be anything special of an essay, outside of how it managed to go over the word limit even without a proper conclusion. All of my typical college essay procedures were utilized to write it, and the bulk of Chrono Cross’s analysis wasn’t my own; instead pulled from this analysis of the game’s environmentalist themes. In some ways, that’s probably for the best, considering I’ve never actually finished the game myself.

Chrono Cross is far from your conventional sequel—compared to Trigger’s brisk Saturday morning cartoon vibe, Cross is a plodding, scattered, almost mournful Saturday night anime of a videogame—but it's also integral to what makes it uniquely good. Making sure your themes are properly emphasized isn’t necessarily conductive to making a smoothly paced experience though; and after scratching my head at what seemed like an endgame macguffin collect-a-thon that was really 2/3rds of the way in, I shelved it and watched a longplay of the game instead.

Conventional knowledge would probably have one think you should at least finish something before you write a +1500 word analysis of it—which I’d also agree with, since simply watching a video of a game will always be too far removed from the experience of playing it. But I dunno, once you get past a certain point and get a good feel for things, I still think you can safely put it down before the credits and still consider it a fulfilling experience. Chrono Cross left enough of an impression on me that I felt like I still had to witness everything and read stuff about it; worse than actually playing it all the way to the end—so in some small way, leaving me with that lingering curiosity makes it a success.

Coincidentally, I did manage to finish one of the games I’m here to write about, which I wasn’t expecting to do: Anodyne, a so-called surreal Zelda lite game; and its sequel Anodyne 2: Return to Dust, which subsumes the 2D-Zeldaness within a 3D world rendered with PSX-crisp graphics and a narrative with layers of meta and subtext.

Zelda is a series I’ve done rarely more than dip my toes into, particularly so for its 2D entries (outside of the DS duology, I’m pretty sure I’ve only completed two?). Until recently, the series’ longtime focus on mechanical puzzle solving, coupled with narratives that aren’t much more than window dressing, makes for games that get uninteresting quick the moment I start banging my head on the wall of a hard puzzle. Anodyne ended up getting lumped onto the same shelf as many of its predecessors—but as an ostensibly weirder experience than anything Zelda has managed to make, the game lingered in my mind much longer.

I don’t want to understate it—Anodyne is a weird game, and in my eyes much moreso than its sequel. Part of this probably has to do with the intent of this initial installment: as said by the duo-dev-team Analgesic Productions in an interview, Anodyne was made by taking the dreamlike conventions of the oddball Link’s Awakening and mashing it up with a pastiche of 16-bit era games.

A lot of Anodyne’s initial parts seem to set it up as a parody—you play as a kid named “Young,” suddenly thrust into “The Land” with assurances that it’s his destiny to save it from “The Darkness” encroaching upon some legendary briar or other, with a broom instead of a sword. Most of the first few areas are typical adventure game locales like a field, a forest, some cliffs, etc; and a lot of the NPCs scattered around are jokes or callbacks to older games.

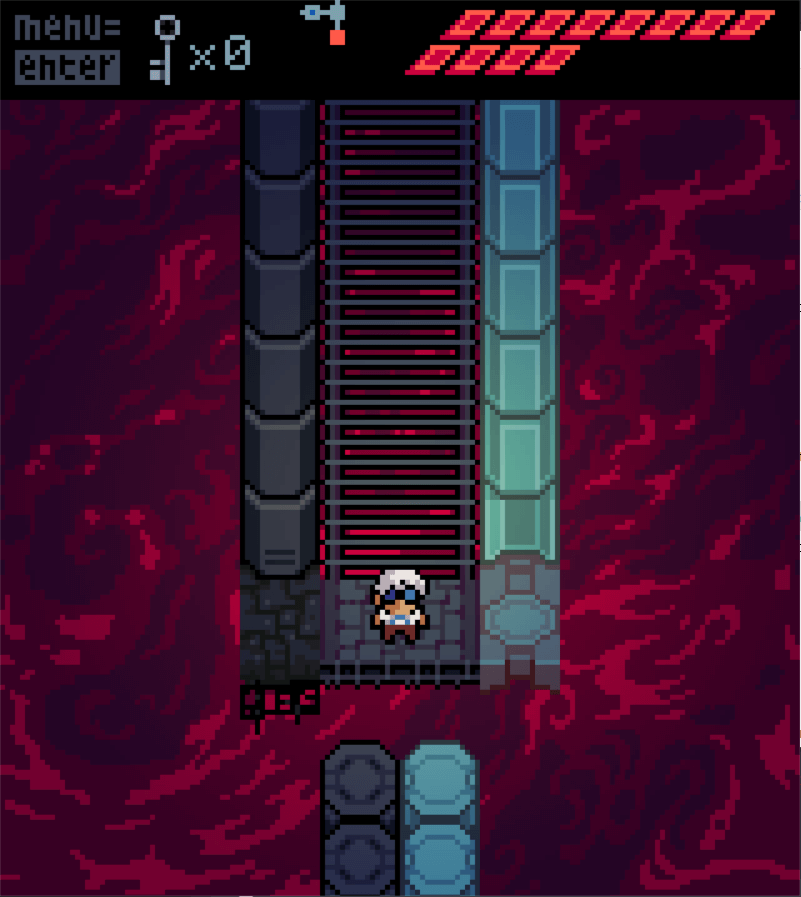

Except in just a few short minutes you’ll go from a portal-filled hub, to a lonely highway, to a forest, each with their own style of haunting music, and you’ll know Anodyne is already priming you for some discordant transitions, which come in spades once you’ve explored for a little while. More modern day settings like an apartment complex or a hotel are scattered around; an unassuming cave can suddenly be filled with dozens of copies of the same expressionless NPC; an average beach can take you to a reddened, withering bog and the grotesque grottos it hides, then suddenly downgrade things to an 8-bit RPG dungeon.

Those aforementioned forest and apartment in particular are bridged by “Young Town,” a black-and-white rendition of a suburb that precisely straddles the line between unsettling and horror. The screen gets grainy, white noise plays in lieu of any music, emotionless human NPCs wander around town as an inconvenience—and, unique to the town, Young’s broom suddenly turns into a knife. It’s not just a twisted fantasy of an open-world game killing spree made manifest though, as some of the townspeople are invincible shadows that chase after Young and kill him in just two hits, adding a dash of dread to what should just be an unsettling curiosity.

What’s strange about Anodyne, and likely the reason I stumbled through it as long as I did, is how much its 16-bit pastiche felt familiar to me. Not exactly recognizable, but familiar—I can’t call to mind what any given visual element is calling back to, but if it as pointed out to me, the disparate puzzle pieces in my head would slot into place. I can wager a guess for a handful of stuff—the cliffs look like a mix between Chrono Trigger and Final Fantasy IV, the design of the leaves and overall cozy feeling of the forest reminds me of Yoshi’s Island, and I think the penultimate area is a riff on A Link to the Past?—but other than those, Anodyne is completely unfamiliar territory to me.

That makes sense, since I grew up with your PS2s and DSes instead of your PSX’s and Game Boys. It’s still intriguing how I manage to recognize so much, how I’m pulling from memories that aren’t my own, probably because of how much nostalgia for the 16-bit era is so ingrained in western videogames culture. I don’t remember if I picked this up from one of Anodyne’s developers or somewhere else, but if you try to call back to mind specific parts of a childhood game you hadn’t played since then, you likely wouldn’t be able to recall the full audiovisual package of a place or moment, as much as you’d be trying to grasp at scattered pieces of it. Makes me wonder what a version of Anodyne from folks who grew up in the heyday of Flash games would look like…

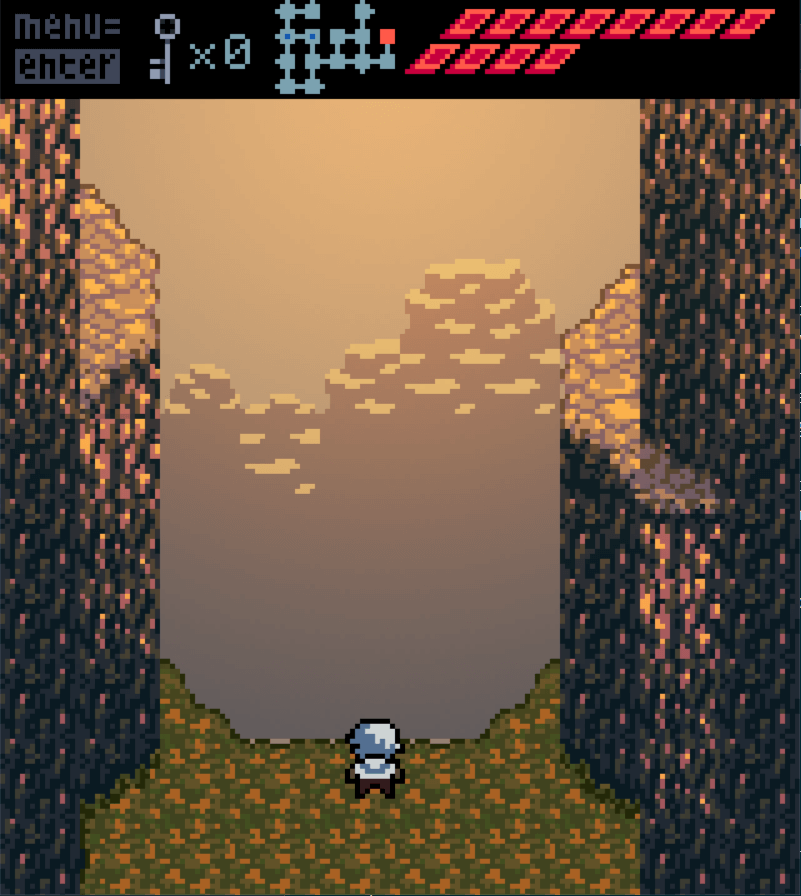

The duality of…environmental design?

On the other hand, ephemeral nostalgia didn’t drive me nearly as much to complete Anodyne 2. Nor could it be, since I have barely any knowledge of early 3D platformers—and nor did it really need to, since Anodyne 2 features a narrative that’s much more overt than its predecessor, but still remains just as queer as Anodyne 1. “Queer” in this case is a pretty multifaceted word, and much more encompassing than the straightforward(?) weirdness of the original. Anodyne 2: Return to Dust is queer in the sense of toning down the surreal pastiche look of its predecessor in favor of more unified series of dreamy and windwept landscapes in its low-poly overworld.

It’s also queer in terms of the emotional journey its protagonist, Nano Cleaner Nova, undergoes. Brought to life by The Center for the sole purpose of purging the “tainted” minds of the inhabitants of New Theland (yup) of the supposedly unclean Dust, Nova quickly learns the nigh-religious devotion demanded by her implanted indoctrination (literally) puts a massive strain on her body and mind. Despite the coincidental death of Guardian Palisade, Nova’s benevolent maternal figure who encourages her to embrace her own individuality (in Palisade’s words: “You are a person, with feelings and needs and desires. I want you to know, Nova, that all of this matters…every part of you! Work and play, joy and sadness, strength and weakness. There is room in the world for all of Nova!”), Nova nonetheless plods onward.

After witnessing more liberating approaches to life untethered from The Center’s influence, Nova begins to question whether the role she plays is for a truly benevolent cause, or if she’s merely another tool for control. In the end, the player can either choose to keep Nova on the path set before her at birth, leading to Anodyne 2’s eponymous version of a biblical rapture, crystalizing the entirety of New Theland and its inhabitants into the “perfect” version of The Center’s vision…or instead confront The Center’s rule, steal away with a new Nano Cleaner who would become merely another arm of the law, and set off for a new life, with a framework of communal nurturing as their guidepost than reprimanding morality.

Anodyne 2 doesn’t necessarily communicate all of this up front. I’m pretty sure I wouldn’t have gotten this much of a takeway, especially since Anodyne 2 was in just as much danger of getting shelved as Anodyne 1 was; until I stumbled across this lovely analysis of the game’s themes over on lotus root records. It’s a good read regardless if you’ve played the game or not, and since it doesn’t touch on everything there’ll still be some surprises left if you decide to pick it up after reading!

Funnily enough, I came upon one of those unmentioned surprises the next time I booted up Anodyne 2 after reading lotus’s piece, and if I didn’t hit a wall where I did, I’m pretty sure I would’ve made a better effort to finish it still. Some of Anodyne 2’s later 2D areas are about the size of your typical Zelda dungeon (save a wholly genre-bending interlude that veers into horror while graciously allowing you to skip it in favor of a prose rundown, something my terribly squeamish self appreciates), yet one of them managed to completely pull me in for completely obvious reasons.

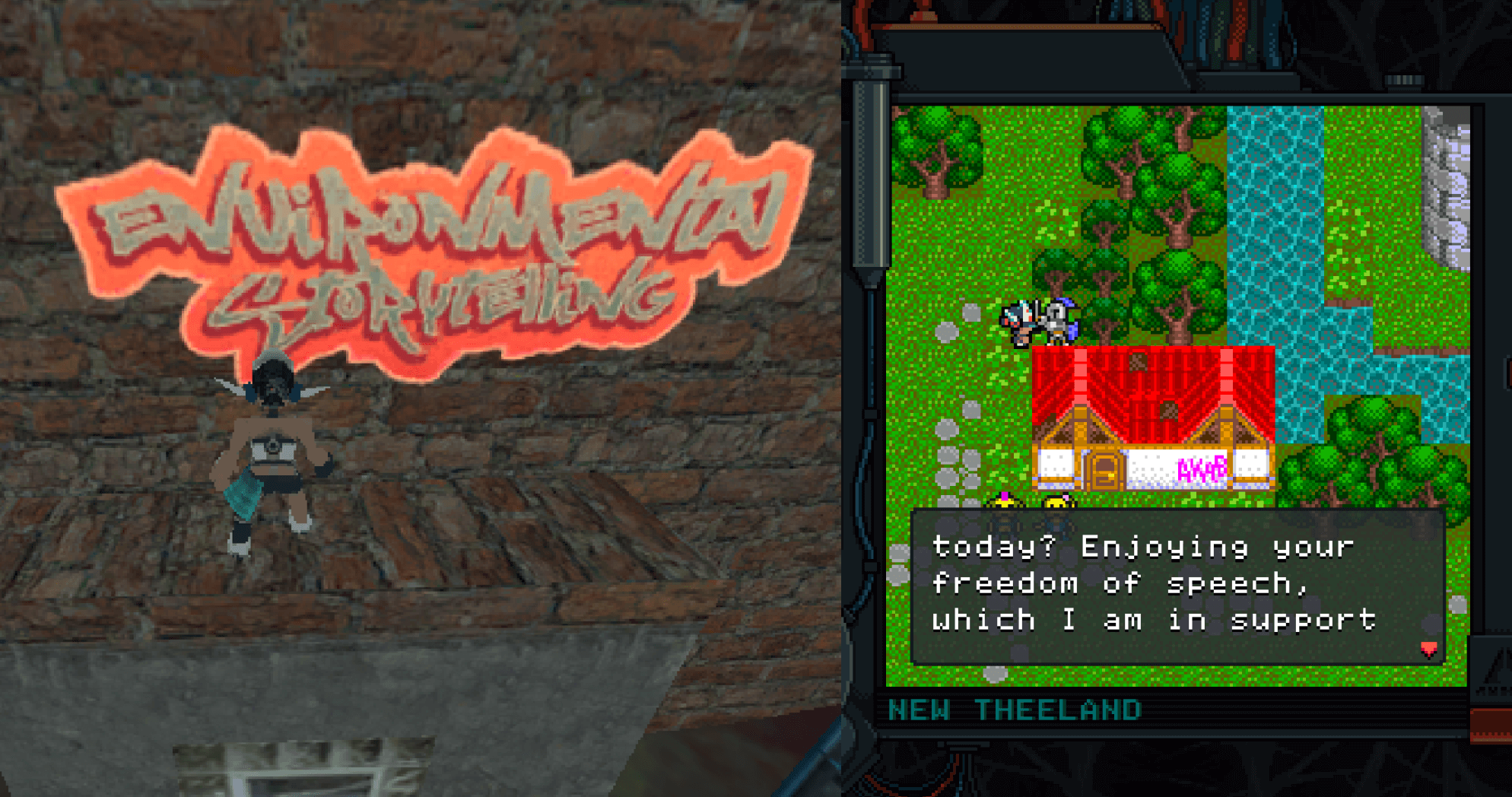

Enter New Theeland (yeeppp), a world-map sized parody of early NES-era RPGs. Instead of over-the-top exaggerations of characters or mechanics, it’s more of a fun critique of the ideologies implied by many JRPGs. Lots of widely-known mechanical gimmicks are played for laughs over outright condemnation, and roles typically considered infallible or unimportant are called into question: your heroes descended from royalty, your faceless guards and their treatment of the citizens they supposedly protect. A first glance at its art style gives the impression of a heavy Dragon Quest influence (and I’m pretty sure the first two notes of its castle track are the exact same as the first Dragon Quest’s town theme?), but overall, the rigid squareness of its tileset reminds me a lot of old RPG Makers.

These prods at convention are some of the most upfront things about Anodyne 2, since just about every 3D area has an NPC that acknowledges they’re all in a videogame in some way. Midway through the game, the introduction of a new NPC and the staple 3D platformer mechanic they brought with them ended up adding the most visceral change to my experience with the game.

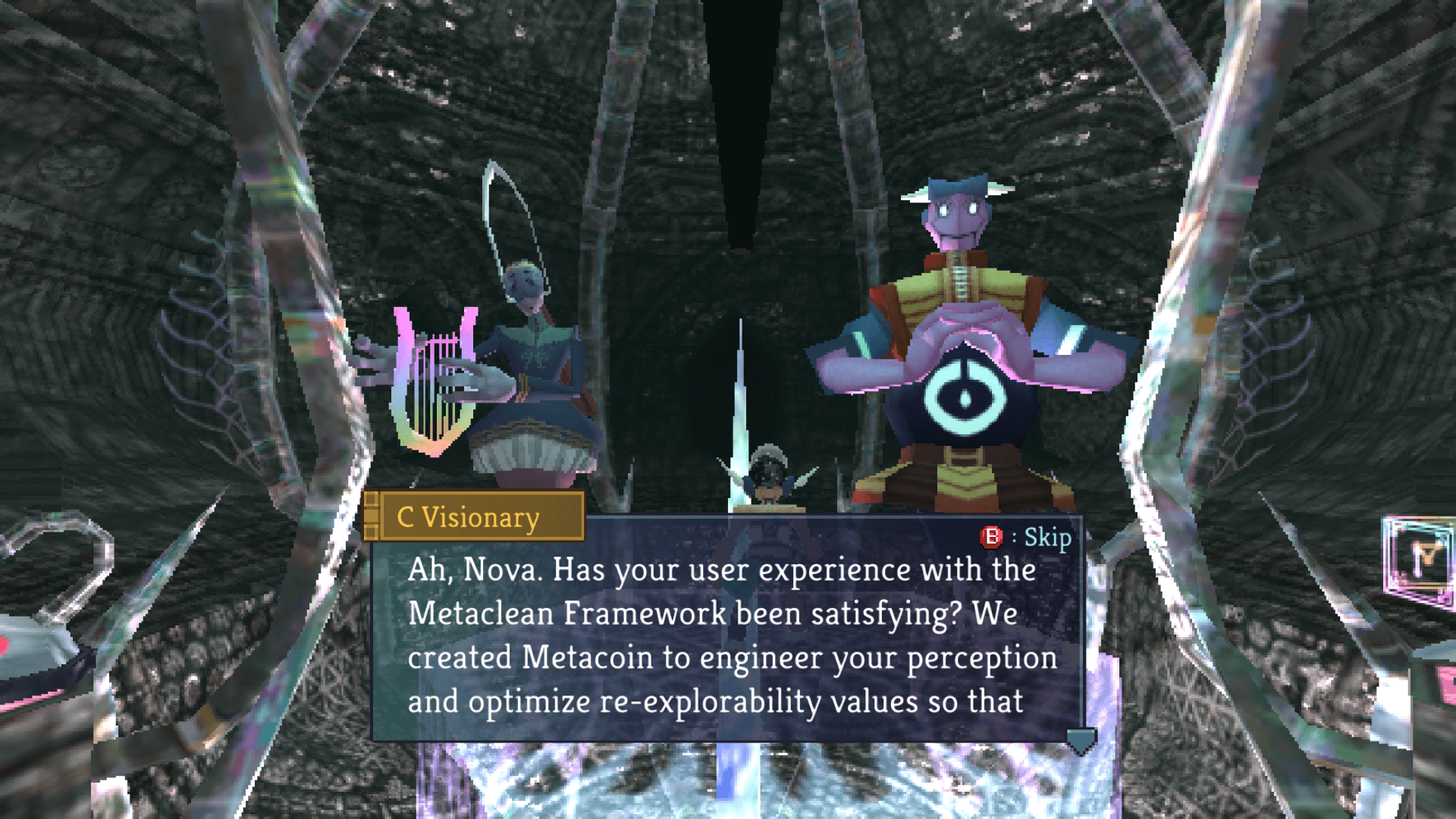

An hour or so after Palisade’s death, Nova finds herself back at The Center again, where someone new is called upon to take the place of her previous maternal figure: C Visionary, a robotic envoy peddling techno-capitalist platitudes about “efficiency” and “revolutionary solutions for a changing world” and whatnot. C Visionary’s appearance is accompanied by the introduction of Metacoins to the world, giving the player an incentive to explore more by collecting a currency that can buy snippets of commentary about the game’s development, be it menu-based logs, waypoints found throughout New Theland, or even placeholder-filled environments left in the game.

This sounds like something that should be a net positive for the experience: the player has more of a reason to tread further and retread old ground, rewarding their curiosity for exploration and knowledge in one simple package. This doesn’t happen in practice—most of New Theland’s locales are so wide open that Nova’s dedicated RC-car form is necessary to get around at a reasonable pace. The Metacoins themselves are placed in scattered, almost random locations, with little flow between batches of coins, meaning you’ll have to deliberately go out of your way the more information you want to unlock.

Whereas before I was following my natural curiosity and taking in the surreal environments of New Theland for the simple sake of exploration, the addition of the Metacoins began to pull all my attention towards the little collectibles. I don’t want to understate the effect of this change on my experience with Anodyne 2—since I don’t actively seek out gamedev knowledge and almost certainly don’t ever plan on making anything in 3D alone, I didn’t have much of a reason to go coin-chasing. And yet, my entire engagement with the 3D environments was warped, the then-dormant completionist part of my brain suddenly unable to go more than 30 seconds without chasing after some silly shining trinkets.

I’m almost sure this is the intended effect though! It’s gotten me thinking about digital spaces in modern 3D games. Meticulously made as any given world can be, how much are we really intended to pay attention to them, with all their mechanics and HUDs overlaid over everything? How many (or few) players ever feel compelled to slow down, to really try and take things in, to appreciate the illusion for what it tries to be? Does it bode well that the process of figuring out how to navigate a space in many games is as streamlined as possible, turning everything a series of ignorable distractions that are only made to hide away or funnel the player the next trinket or waypoint in sequence?