Monsoons, Monodies, Magic, Midgar, and Mountains

17 January 2021

To me, 2020 was—in what's a massive understatement for 80~90% of the rest of the people living on earth—a pretty weird year, all things considered. Thanks to my stupidly fortunate circumstances, all of the relatively reclusive habits I had been trying to recover from suddenly became essential when the pandemic took hold in America. Somehow, I managed to come out of things with an English degree (job limbo here I come), half a fanfiction duology finished (these things are fuckin’ hard to write even when high off fandom energy, though coming down is probably what’s really making it difficult), a smattering of Japanese learned (with no idea of what to do with it other than keep learning?), and only a slightly-higher-than-average stress level.

At least the videogames were good, I guess. Here's five of my favorites from this year, along with my favorite track from each in the spirit of a certain game.

Risk of Rain 2

From a purely mechanical standpoint, Risk of Rain 2 is about chasing a sugar high.

It took a while for me to figure out how to classify this game, so here’s the lowdown if you’re not familiar: Risk of Rain 2 is a roguelite that escape-pod-crash-lands you as one of ten unlockable starship-catastrophe survivors onto the alien planet of Petrichor V, with the obvious goal of escaping its perils by way of the randomly generated items and shrines of varying effects. But, since I told you what the game was really about just two sentences ago, this probably isn’t what you’ll be aiming for most of the time. Heck, as an early access game, escaping the planet wasn’t even an option until the addition of its final boss in a 1.0 release, unless you wanted to obliterate yourself into nonexistence to atone for all the havoc you end up wreaking on the poor planet’s menagerie of deadly monsters if you play it well.

Risk of Rain 2’s brand of hurricane-turbulent difficulty is a little different from typical roguish games. Instead of dropping you into the storm from the jump, a run starts off as a relatively lenient drizzle that gradually rains bigger drops in sync with an in-game timer, increasing the strength of Petrichor V’s monsters directly in line with time spent playing. Combine your frailty with the game’s major method of powering yourself up, chancing chests for a variety of offensive and defensive items, and the game becomes a tightrope balancing act of getting what you need to weather the onslaught of increasingly-angry-and-numerous alien anticolonists.

The randomness forces you to pick and prioritize your items to support whichever one(s) you have a high number of or one that’s rare enough to serve as a build’s foundation, turning the steady stream of dopamine you get from the numbers going up in any other modern action game into a constant seesaw of loot box lotteries. Be fortunate enough to get a good combo of items (say, a summonable bubble of fire that constantly damages yourself and enemies around you while also constantly activating an item that attacks surrounding enemies as you take damage), and you’ll go from a frail sack of meat and/or metal to your own kind of hurricane that can decimate the most elite of enemies…while still remaining pretty frail, since the ballooning number of non-fodder enemies will have strengthened themselves into their own storms by then.

I’ll admit, this game was a fixture throughout my year because it hit that sweet spot of brain-stimulation/listening ratio that makes it great for listening to podcasts to, but Risk of Rain 2 has the extra appeal of its (currently unfinished but still) extensive lorebook giving texture to its universe. I generally don’t find sci-fi or futuristic settings to be very interesting—and probably wouldn’t have ever given this game a second glance had a friend not invited me to play with them otherwise—but surprisingly, I’ve found myself pretty drawn into Risk of Rain 2’s universe, enough to have a couple of barely-started drafts of fanfiction.

The gist of its narrative framing is that an intergalactic Amazon has a string of research excursions to Petrichor V that keep getting destroyed, and the boxes that all your items come from is just cargo scattered from the first ship that crashed there. It adds what I think is a nicely-nuanced justification for the time = difficulty shtick: with you running around killing everything that moves after the planet already told the first two groups of colonialists to fuck off, no wonder it doesn’t take long for Petrichor V to seem like it hates your guts.

Favorite track: ...con lentitud poderosa

The World Ends With You: Final Remix

I can’t remember where I heard this quote from, but some say that your experience playing a game doesn’t begin when you boot it up, but instead the first time you hear about it. Depending on what “hear about” means in this case, I started playing The World Ends With You long before I actually got a copy of the game, by way of listening to its soundtrack.

It’s hard to pin down exactly how I found it for the first time (probably by stumbling across one of the so-called “Kingdom” remixes that would later be featured in Kingdom Hearts 3D), or even how to describe what I like about its music because of how wide its range of genres is. Going off my favorite tracks, there’s electro pop (Déjà Vu), American hip hop (Detonation, Game Over, Twister’s Final Remix), Japanese hip hop (Owari-Hajimari), rock (Tatakai, Three Minutes Clapping), J-rock (Hybrid), whatever the heck Ooparts is, and probably even more than that. I can't remember any song driving home the emotions of any particular moment, but all of them are so lusciously earwormy that they managed to stick in my head before and after I had put the game down.

Funnily enough, I almost believed I never would finish this game at first, because whooo boy, this game was rough, even on the new-fangled Final Remix port for the Switch. Going off Badru’s scale of difficulty, The World Ends With You has always been a “kind” game, since you can save any time you want and there’s no direct penalty for losing battles; but just as the game is about the struggles of connecting with others, getting the hang of it’s battle system (or in my case, feeling like you’re making tangible progress with learning) is definitely difficult.

Without the two screens of the original DS version, the double-arena light puck-juggling to work both characters is heavily simplified into touchscreen gestures. Much of the intensity is lost in the transition, since you no longer have to keep track of both screens by controlling a freely-running Neku with the stylus and his partner on the top with the DPad/ABXY, but I found that the Switch version has a couple of it’s own quirks to adapt to. Since the Joy-Con controls are about as precise as a five year old with a Wii remote can be, I had to remove from my Switch and hold it like an oversized smartphone to play, and you’re still moving around with the same gestures used for a ton of attacking pins, some practice is still needed to get through things.

Still, even if the touch-based partner system is a poor imitation of the original, I thought at least a tiny bit of its uniqueness between each of Neku’s companions was retained. Shiki and Beat are mostly friendly towards Neku when partnered up with him for their portions of the game, so their motions were relatively simple to integrate into my playstyle; but Joshua, self-assured and prickly as he is, heeds only a specific downward slash of your finger and nothing else.

Aesthetic footholds and thematic takeaways aside; The World Ends With You sticks out in my mind after the fact for the conundrum it presented me. Having favored a specific kind of JRPG for most of my life, designed with mass appeal in my by giving you plentiful resources and a wide range of abilities, I’ve recently been drawn to games that are made to be challenging even for experienced RPG players by limiting those options (mostly thanks to the works and blog of sraëka-lillian, and something I’d like to devote another post for delving into eventually). While played in a completely unique fashion, The World Ends With You should’ve been a game I’d have been primed to enjoy…but instead, I found its systems off-putting enough that I couldn’t get more than a couple hours into the original game after multiple attempts! It’s pretty on-the-nose about its themes that you won’t miss out on anything even without the original battle system driving things home, so despite the supposed contention around the release of Final Remix, it’s existence is definitely a net good.

Favorite track: haha you want me to pick just one favorite from all those haha

Ikenfell

(CW for mental illnesses, along with some vague spoilers.)

Ikenfell is one of those special games where after watching 10 seconds of its initial trailer I immediately thought this is 100% my jam. Cheery, kid-friendly, crisp pixel art-rendered visuals? Check. Tactical RPG battles mixed with timed action mechanics? Little bit of an ehhh to the former, but a yep to the latter. Peppy orchestral chiptune soundtrack featuring full-blown vocal compositions? Awwww yeah. Magical school shenanigans that unfurl into surreal mysteries that balloon into world-ending crises? Well, the former usually ends up being a turn-off for me in novels (this has nothing to do with that series since I’ve literally only read the first book, my lizard brain is just averse to fantasy academies for some reason), but the latter’s about as par for the course as it can be in any RPG, so go ahead and inject that stuff into my veins.

Playing through this game gave me the good ‘ol warm and fuzzy feels just as I’d expected—but what I think sets Ikenfell apart from a lot of games made to evoke those vibes is how earnest it is about the struggles of its characters. There’s a lot of mental health issues explored in Ikenfell, but an equal amount of care is taken to show how they actively affect someone’s lived experience, even going as far to be constantly yet subtly reminding you of them as you play.

A couple months ago, I ran into a video essay dissecting how, contrary to the public perception of the genre, that oft-maligned turn-based JRPGs have pretty much always been designed with the link between gameplay and narrative in mind, specifically in how characters’ toolkits and underlying stats support their personalities or changes throughout their stories. In this fashion, I’d say Ikenfell is an absolute pinnacle at this, since important aspects of every playable character is evoked in each of their combat designs.

Maritte, the game’s protagonist and sister of the plucky troublemaker at the heart of Ikenfell’s story, is an Ordinary-turned-fire-mage due to plot strangeness; and with the outside perspective she brings to the school’s troubles she gives most of the playable cast a emotional leg-up, along with the ability to increase their power in battles to boot. Petronella has self-esteem issues written all over them and is primed for a support role with their alchemical tinkerings, just as you’d expect—but they’re also the only party member with immediate healing skills, making them absolutely essential in tough battles (with a fitting payoff at the end of the story). Rook, a composed and astute bookworm with a theme called “Between the Lines,” has a toolkit made for reading between those lines: stealing items from enemies, seeking out weak targets, and if you can read movement patterns well enough, hindering enemies with planted traps.

Pertisia, when she initially joins, is completely antagonistic towards the initial trio despite being defensively-oriented with her protective crystals—turns out a friendship gone sour with Maritte’s sister involved a traumatic event that made her averse to being touched, physically or emotionally. Ima, Ikenfell’s most popular professor, ends up taking the lead for a while when Maritte falls into emotional shock from a bombshell mid-game reveal; top of the class as ze was, zir toolkit is the most well-rounded in the entire game, hitting every point of the attack-heal-support trifecta. And Gilda…well, take a look at what archetype is missing, listen to her theme, and I think you’ll figure out what she showcases pretty easily.

As I sit on my time with Ikenfell, I’m finding that I like it more and more—even if, as the head developer has admitted themselves, it’s not perfect. Frankly, the only trouble I had with the game is that the cues for timing skills and defending from attacks feels rather inconsistent across the board. But since the only games I can personally size Ikenfell up against are the Mario & Luigi RPGs (may AlphaDream rest in piece ( ̄^ ̄)7), the huge gap in resources from a Nintendo-backed game means this probably isn’t a fair comparison—and there’s already a wealth of accessibility options to tailor Ikenfell to how you want to play it making this mostly redundant anyway! (unless you’re really good at internalizing these kinds of timings I’d recommend playing through it on Semi-Auto for a fair challenge though)

Favorite track: Once Upon a Universe

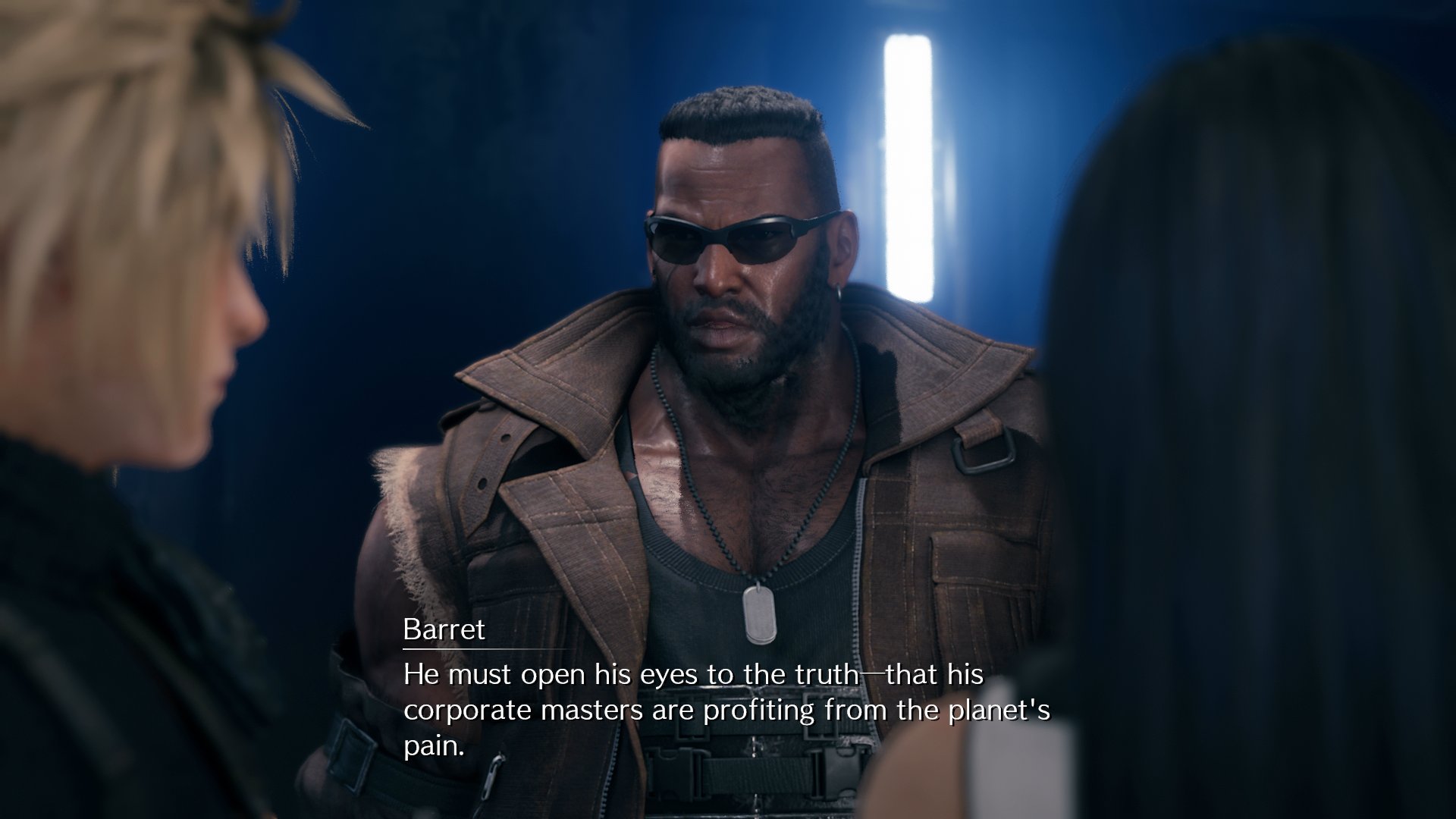

Final Fantasy VII Remake

If someone asked me, “hey JW, what’s your favorite videogame series?” I’d probably respond with Final Fantasy, simply because other than my fond childhood reminiscences, it’s probably the series that’s driven me to telling stories the most. Despite what that might imply about the videogame I’m currently writing about, Final Fantasy VII Remake has almost no meaning to me as a cultural touchstone.

Since I was still a year away from being born when the original Final Fantasy VII was released in 1997, most of my nostalgia for the series lies in bumbling three-quarters of the way through FFX and idly grinding the main cast of FFII—yes, the actual Final Fantasy II—to absurd levels in the iOS port, making VII Remake not much more than “a mako-reactor-souped-up version of a videogame I’d always been aware of and eventually played two years before this came out.” (for those curious of my favorite, I am, predictably, a Final Fantasy IX hipster). Without any firsthand knowledge of the legacy of VII, I didn’t really expect much from Remake other than that, so my expectations were fulfilled pretty handily.

It’s exhaustively documented how the original FFVII’s massive success was the result of a blue-moon-and-stars-aligning junction where Squaresoft was given the opportunity to showcase the newest leaps in 3D technology. What’s a lot less documented is the ridiculous amounts of money poured into it: over $140 million USD across development and marketing. With the skyscraping cost of modern AAA videogame production, I wouldn’t be surprised if 10 hours of Remake’s content cost as much as the original FFVII alone, and when you multiply that $140,000,000 by four, well…Square Enix probably could’ve done plenty of good in advancing the politics the game espouses in the real world.

And though I’m merely an outsider looking in through the glasses of others, what’s a only hushed whisper is how these high costs demand a specific kind of beaten-path design for them to even have a chance of breaking even. For a AAA game to be successful, there’s a specific blueprint that risks financial ruin if deviated from: a menagerie of tried-and-true gameplay mechanics that are increasingly lifted from other successful big games, a narrative that sands off the complexities of its world and characters into an inoffensive and easy-to-understand-and/or-market smoothness, and enough checklists of content to keep an office worker busy for a week.

What makes Final Fantasy VII Remake remarkable to me—even though its immense prestige guaranteed its success—is that while it absolutely checks all those boxes in some way (particularly with some of its mechanics), it’s a game taking a lot of risks.

Instead of skirting around the politics that are philosophically at it’s heart but mostly lay in the sideline of people's memories from the original, Remake has them pretty close to front and center for most of the game. Even more remarkable—if not an incredible flex, especially considering what my current project is based off of—Final Fantasy VII Remake is a struggle against it’s own fanbase, the untamable clamor to be the exact thing people waited 23 years; but even as it initially satisfies most of those expectations, Remake is also questioning why the hell it should be an exact reproduction in the first place. It’s unquestionably a ballsy route to go down, because despite the black hole of profit margins and fan fervor, Final Fantasy VII Remake is not a one-to-one remake of the first four hours of the videogame Final Fantasy VII (oh god how long is this gonna be stretched) with a shiny coat of paint, but instead a videogame about being the remake of Final Fantasy VII.

Hopefully, those gravitational pulls of destiny Cloud and co. seemingly freed themselves from don’t suddenly reestablish themselves and toss them back on too similar a path in Rebirth or Reunion or whatever the later games will be called…

Favorite track: Seven Seconds till the End

(I literally cannot find a video with just the 2 minute song on it's own so you get to watch part of the spoilertastic ending. A lot of the coolness factor is lost without hearing it in context though so…)

Celeste

You ever stumble across a piece of art trying to pass something on to you?

That’s a silly question, even the for the media most pulled in by the black hole of mass appeal I just mentioned a section ago, there’s probably at least a creator or two who tried to impart whatever lessons they learned about the experiences they’ve attempted to convey onto you as you interact with it. Sometimes, if your experience meshes well enough with a work, you’ll have found something that sticks with you for a long time.

This usually ends up being the limit for, I’d say, around 95% of the art someone interacts with, but that last 5% I think, has an even more profound effect, even moreso if you don’t know what to expect going into it.

It’s a little hard to describe my last experience with this, but I’ll try: you ever stumble across a piece of art that just…pops the foggy lenses of your glasses out and replaces them with a spotless pair as you’re using them, without you even realizing it? Crystal-clear enough that an enormous tangle of personal issues you’ve been grappling against your whole life suddenly become a lot easier to navigate without being prickled?

For me in 2020, that was Celeste.

Now, despite all of my reverence, realizing all this wasn’t some emotional revelation that drove me to tears—though the moments when Madeline and Little Goth (this is a better name, why is her “official” name Badeline) gradually reconcile bring me to that point pretty easily. But the way this videogame put a bunch of things I’d been dealing with for so long into perspective so entirely and elegantly is…indescribable enough that I can only really say kinda crazy, for now.

There’s a sublimely crafted platformer and a soundtrack that’s been fully assimilated into my mental eardrums playing a part in things too, but everything about this game has probably gotten mountains of praise since releasing 3 years ago, so there’s not much I can say about Celeste that’s already been said. Heavily relating to a transgender protagonist as a cisgender dude without knowing it is pretty rad, though.

Oh yeah, apparently Celeste, Ikenfell, and Wandersong—which I haven’t played—all shared their beginnings in the same living space. I guess I’ll be obliged to complete this trifecta eventually…

Favorite track: Resurrections